Last Updated on October 18, 2023 by Birth Facts

This page summarises the supporting evidence sources for my estimates of the risks for newborn’s health associated with different modes of delivery. Where possible, I have tried to use estimates given in systematic reviews or meta-analyses, which try to capture the weight of the literature on a topic rather than individual studies. I focus only on the risks in high income countries. The risks in low income countries may be different.

The discussion here will be more technical than on the page outlining the risks of different modes of delivery.

Absolute risk vs relative risk

In trying to capture the risks of different modes of delivery, I focus on absolute risk rather than relative risk. Relative risk tell you how much higher a risk is in one group compared to another. This is not very informative because it does not tell you how large the risk is overall.

For example, it may be true that walking around with a metal tipped umbrella increases your risk of being struck by lightning by 500%. This doesn’t tell you anything about how risky walking around with a metal tipped umbrella is. To know that, we need to know the risk of being struck by lightning without a metal umbrella. Since the risk of being struck by lightning is extremely small, increases in this relative risk don’t matter very much.

For this reason, on this website, I report absolute risks rather than relative risks. Absolute risk tells you how many of a certain types of outcome we should expect to see in a group of people. For instance, it says that for 1,000 women giving birth vaginally, around 200 will suffer stress urinary incontinence.

General notes about the evidence

Where possible in this evidence review, I use risk estimates from the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). NICE is a body that evaluates the risks of different medical interventions by surveying the empirical literature with the aim of finding high quality studies. NICE evaluations in turn determine prioritisation and informed consent policies in the UK National Health Service. The evidence reviewed by NICE typically focuses on high-income countries, and so is relevant to all high-income countries, not just the UK.

I use the NICE evaluation because NICE is an internationally respected global health body that carries out extensive, rigorous and publicly available evidence reviews of all medical procedures. I am not aware of a better resource written in English.

The drawbacks of NICE estimates, and in general the evidence in the field of birth trauma, are as follows:

- Many studies do not disaggregate different modes of delivery. In particular, for many potential risks, studies do not separate operative from unassisted vaginal delivery; different types of operative delivery (forceps or vacuum); different types of c-section (planned or unplanned). These all have importantly different risks.

- In particular, in its review of c-sections, NICE is answering a different question to the one I am answering here because it is primarily focused on the choice between planned vaginal birth and planned c-section, and not on the other possible modes of delivery.

- NICE does not evaluate many important risks, such as levator avulsion and pelvic organ prolapse. The reasons for this are unclear.

- Many studies report only relative risks, not absolute risks.

- Many studies only have small sample sizes or are biased for other reasons. NICE classes all of the studies used in its evidence review as low or very low quality (Table 7).

One important general issue with the literature on the risks of modes of delivery is that it is ethically and practically impossible or very difficult to run a randomised control trial on modes of delivery. Consequently, all of the studies are observational. This means that there are risks of confounding, which may be difficult to correct for. For example, women who are more likely to have an operative delivery or emergency c-section may be at greater risk of some bad outcomes independently of the mode of delivery. A study that attributes all of these bad outcomes to the mode of delivery would overstate the risk.

Second, there is a risk that the controls themselves introduce bias if the control is not actually an independent cause of a particular outcome. For example, a study comparing operative delivery and emergency c-section might adjust for maternal income when assessing certain outcomes. But it might be that income only has an impact on the outcome because better off women are more likely to choose e.g. an operative delivery, rather than because income independently affects the outcome. If so, the control would introduce bias.

In spite of this, observational evidence is all we have, and in some cases clear conclusions can be drawn from it about the causal effects of different modes of delivery.

Problems with confounding

Prior to labour, no-one plans to have a forceps or ventouse delivery or an unplanned c-section. These will only be performed if medically necessary or if the mother is too exhausted to give birth vaginally without assistance. Consequently, children delivered this way are likely at much greater risk even if that risk is not caused by those modes of delivery. Correlation is not causation. This means that it can be misleading to compare to compare the outcomes for these modes of delivery, and attribute any additional risk to those modes of delivery.

In the case of newborn death, the risk of confounding when is particularly acute when comparing forceps, ventouse and unplanned c-section to the alternatives. Babies delivered in this way may be at higher risk of injury or death, but often these procedures are performed in order to prevent serious harm to the baby. Thus, their causal effect is likely to reduce the risk of harm to the baby.

When comparing unplanned c-section with planned vaginal birth, these concerns about confounding are less severe but still an issue. Some planned c-sections are performed because the baby is at risk. However, for c-sections that are not medically indicated, the risk of newborn death is still higher than for women who plan to give birth vaginally.

Newborn death

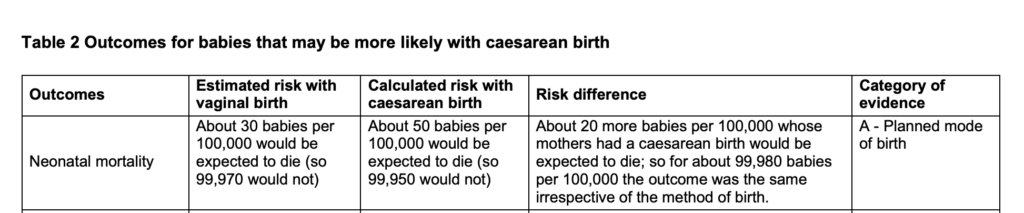

The data on newborn death is from the 2021 UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence guidance on the risks of different modes of delivery. Table 2 in Appendix A of that document summarises the relative risks of caesarian versus vaginal delivery for newborn mortality:

The basis for this estimate is summarised in the National Institute of Clinical Excellence Evidence Review A document on the risks of caesarian birth, and refers to MacDorman et al (2008) ‘Neonatal Mortality for Primary Cesarean and Vaginal Births to Low-Risk Women: Application of an “Intention-to-Treat” Model’, Birth.

I have been unable to find reliable data on the risks of forceps, ventouse and unplanned c-section that adequately reduces concerns about confounding.

Asthma

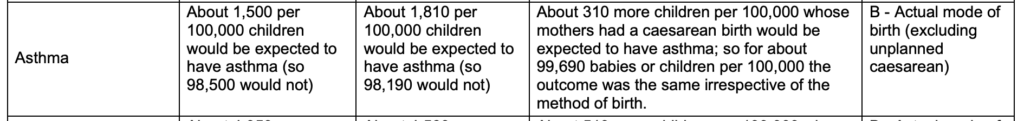

The data on asthma is from the 2021 UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence guidance on the risks of different modes of delivery. Table 2 in Appendix A of that document summarises the relative risks of caesarian versus vaginal delivery for asthma:

The basis for this estimate is summarised in the National Institute of Clinical Excellence Evidence Review A document on the risks of caesarian birth, and refers to Huang et al (2014), ‘Is elective cesarean section associated with a higher risk of asthma? A meta-analysis’, Journal of Asthma